- Home

- Constance O'Keefe

A Thousand Stitches Page 2

A Thousand Stitches Read online

Page 2

“Isn’t it something about a bride and a boat trip on the Inland Sea?” said Morgan. “My Japanese is rusty, but—”

“Yes,” said Akiko, “it’s the story of a young woman leaving her small island and her family, including her little brother, to travel to another island to marry.”

“Ah,” said Morgan.

“It’s a love match,” said Akiko, listening as the second verse shifted pace, the strings swelled, and the singer’s voice edged toward but never quite into tremolo. It reminded Akiko of “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” which she had heard in a student production of Carousel the month before. As much as she thought it was ridiculous, she melted as Julie sang of her Billy’s love beyond death and time, using the same vocal techniques Rumiko Koyanagi was using as she sang of the small boat rounding the cape, the sunset glow, the promise of a clear day on the morrow, and the hopes of the couple for their future. The cloying sentiment was the same, the swelling of the violins the same, “Walk on, walk on, with hope in your heart…”—“Don’t cry, little brother, you’ll be fine with Mother and Father…”

“Sam, Sam, listen to this song,” Morgan called, but by the time Sam finished what he was saying and turned to Morgan, the song was winding down: the violins faded and the sound effects—the cries of Seto sea gulls—brought it to its conclusion. “You don’t know this song?” Morgan asked.

“No,” said Sam. He called the waitress over. She explained that the tape would loop back to it in about an hour. When Morgan and Sam both began telling her about their childhood in Matsuyama and the many ferry trips they took across the Inland Sea, she smiled and said she’d ask the manager to reset the tape.

She was back in a few minutes and was saying, “He’s agreed to reset it. He said he knows the area himself,” as the tape squeaked to a stop. There was a moment of silence before “Seto Bride” began again.

Everyone listened. The manager came and stood by the big round table to listen with his customers. Morgan and Sam translated bits as the song flowed past them. Pauline asked for a complete explanation when it was over, and the two old friends did the best they could. “Akiko says it’s about a love match,” said Morgan.

“Claire saw the Inland Sea the year she taught in Japan,” said Sam, “but for the rest of you, that treat still lies in the future. I’m so glad Akiko and I decided to go back to Japan. It’s time for me to slow down. Perhaps I’ll be lucky enough to end up at a university in Matsuyama again.”

“It is tranquil and beautiful,” said Claire. “It must have been a great area to grow up in.” She looked at Akiko as Morgan and Sam nodded. Akiko caught her eye, and turned away, smiling at Morgan, and responding to his latest comment.

Please, please don’t let Claire or any of the others see my panic. I think I’m keeping it off my face. Just be calm. It is time to go home. I would love to see my sisters. And he has three good possibilities for jobs. We’re just as likely to end up in Tokyo or in Himeji as we are to end up back in Matsuyama.

She remembered another sukiyaki dinner that she had prepared when Claire had come back from her year in Japan. Claire had described her trip to Shikoku, where she had visited Takamatsu and had climbed the steps all the way to the top of Kotohira Shrine in nearby Kotohira before traveling to Matsuyama, where she toured the city and the hot spring at Dogo.

“I’m sorry I didn’t bring you anything special from Shikoku,” Claire had said to Sam.

“What I want is some fresh sea bream from the Inland Sea,” he replied, “and that’s something you couldn’t get through customs.”

Claire had helped Akiko clear the dishes after that sukiyaki feast and had said, “Akiko, you don’t seem as excited about Matsuyama as Sam does. Isn’t it your hometown too?”

“Yes,” she had said, “or at least sort of. I’m from a small mountain village in a remote corner of the prefecture. But I’ve never enjoyed the best opinion of Sam’s family.”

“Why, what could be the problem?” Claire had asked.

“Oh, it’s a long and complicated story,” said Akiko. “But I have no regrets. I was lucky enough to have a love match marriage at a time when they were virtually unknown,” she said as she closed the door to the dishwasher and shook out a tea towel.

As Sam continued to talk about Matsuyama and his job prospects there and in other Japanese cities, Akiko was overwhelmed again. Sam’s mother had refused to meet her on their first visit to Matsuyama as a couple on a Christmas break from Ohio. She remembered walking the short distance from the department store back to the hotel as the light faded from the afternoon sky and fat botan yuki peony snowflakes fell. Her packages, with presents for the children of her sisters and her friends back in Ohio, were heavy, and the snow, so unusual in Matsuyama’s mild winters, stuck to sidewalks, seeped into her shoes, and soaked her coat. She sat alone in the hotel room drying out and waiting for her husband to come back. The weight of the hometown values and the social system she had defied pressed down on her.

Her proud, strong mother-in-law went to her grave having never acknowledged her second daughter-in-law. The next year, Sam’s father visited Ohio. He was a pleasant elderly gentleman who enjoyed being in the States again, but was lost without his wife. Akiko had waved goodbye at the airport in Columbus. Sam went with his father to San Francisco and saw him off from there before coming back to Ohio. His father was dead before the end of the year, and Sam went alone to the funeral. When he returned to Ohio, Akiko had thought that that was the end of Matsuyama in their lives.

But Sam had grown sentimental in the past few years. He had been on a few professional visits, and Matsuyama now seemed to be number one on his list as he considered jobs in Japan.

“After I’ve chosen my new job and we go back to Japan at the end of the next academic year,” he was saying, “we will have spent a total of eighteen years here in the States. I think that my last job in Japan will be a nice counterpart. If I’m lucky, I’ll have another eighteen years—or more—to work in Japan.”

Akiko smiled and thought how glad she was that she was going to stay in Tokyo with her sister while Sam went to visit Matsuyama to talk to the officials at Ehime University. Stop fretting. You defied them—all of Matsuyama—before. You can do it again if you have to. And right then and there she decided that if she had to go back to Matsuyama, she would do so with her head held high. Her life in the States had been a grand adventure. She could walk through any storm she had to.

A month later, Akiko opened the china closet and took out the parcel from the crematorium. She sat at the table and slowly untied the white furoshiki. The box inside had a white paper wrapper with religious symbols. She opened it, knowing that inside the drawstring bag she would see exactly what she didn’t want to see, what she had seen the day she brought it home. She told herself she had to do what he wanted, had to get it done by his birthday. And she had to have this taken care of before she could deal with the manuscript.

She went to the kitchen for the extra suribachi and surikogi mortar and pestle still in their box from the pottery shop. She placed them on the dining room table, remembering the drinking party and how happy it had made her to hear Harumi read Katherine’s letter. She went back to the kitchen and boiled water for genmaicha, her favorite tea, and told herself she had to get to work.

Her hand slipped. She applied more pressure, leaning all her weight into it, but the entire bowl slipped from her grasp. She thought she had broken it but then realized the bowl was fine; it was her finger that was hurt. The scrape bled on the chunk of bone as she picked it up from the floor and put it back in the box. When her hands stopped shaking, she went to the phone.

“Ne-san, I started that job I told you about when you were here. I can’t do it.”

“I’ll take the next train. Wait at your counter,” was Junko’s only response before she hung up.

At two-thirty Junko came through the ticket barrier. Looking determined as usual, she marched up to the tourist information count

er where Akiko was talking with Ichikawa-san. Akiko introduced her big sister and explained that she had come to visit from Osaka.

As they walked away from the counter, Junko said, “Taxi. I’m carrying too much for the bus.” Along the way, the taxi swung by the Castle, and Junko said, “Can’t say that I mind seeing the White Heron when I come here. It really is beautiful and looks great in the fine weather.” When they pulled into the entrance to Akiko’s condo, Junko said, “Oh, little sister, I have news. I read my newspaper on the train. Shotaro Miyazawa has died. Big funeral tomorrow. I guess it’s a major event for corporate Osaka.”

“So Michiko’s a widow now too,” Akiko said.

Junko slipped out of her shoes in the genkan and began pulling things out of her shopping bag. “Here’s the article from the Osaka paper. And here are some Kobe cakes. They sell them in the department store in Osaka Station now. It’s a plot to make me even fatter. And here’s a new suribachi and surikogi. I decided that’s probably the best way to do our job.”

“I have an extra set too. Maybe we can finish quickly.”

They had tea and ate some of the Kobe cakes before they began. They picked big chunks of bone from the box with new chopsticks. “Don’t think,” Junko said, and she went first. They took turns wrapping the large chunks in the white furoshiki and smashing them with a hammer. Then they began grinding.

I’m making my husband dust, Akiko thought. Was this the hand I held as he lay dying? The hand he wrote me letters with? The hand that held mine as the plane landed at Narita? So what if it’s an unseemly public display of affection? She could hear him whispering in her ear.

When Akiko stopped grinding, Junko looked up and saw tears brimming in her sister’s eyes. She chose that moment to launch an old family favorite. “Remember the time Farmer Kiriyama got drunk and almost drowned in the rice paddy?” Akiko shook her head, trying to will the tears away. Junko kept grinding and continued, spinning the story out, embellishing and elaborating the saga of the Kiriyamas, as tears spilled down her sister’s face.

Slowly, Akiko was drawn into the details of the misadventures of their childhood neighbors and recovered enough to join in, “No, you’re not remembering it right. The father only lost one of the boys in the train station in Matsuyama, not both of them.”

As the afternoon light was fading, Akiko’s hand slipped again and again a piece of bone landed on the floor. As they crawled about looking for it, Junko grumbled about how stubborn her brother-in-law always had been and how he was still being difficult. Junko found the bone under a corner of the rug. She held it up and sat back on her heels. “Now how do I get my own old bones up off this damn floor?” They laughed and helped each other up. When they were back in their chairs, Akiko’s laughter turned to tears. As Akiko cried, Junko made more tea. By the time they finished the tea, Akiko had recovered and they began grinding again. They worked in silence until nine o’clock.

Junko said, “Okay, now we have ashes—or at least something more like powder than chunks. What about the suribachi and surikogi?”

“Put the ashes in here, and give it to me. And put both of the suribachi and surikogi in the box your set came in, and wrap the box in this,” Akiko said, reaching for a faded indigo furoshiki from the drawer below the shelves of the china closet.

After Junko poured the ashes into the drawstring bag, Akiko stood, wrapped the box in the white furoshiki from the crematorium, and returned the ashes to the china closet. She then reached up to the top shelf and took out two crystal tumblers and Sam’s single-malt scotch. “This is not a beer occasion.”

As Akiko was putting the tumblers and the scotch on the table, Junko, struggling with the box said, “It won’t work. The two sets are too big.” Akiko took the two suribachi from her sister, wrapped them quickly in the indigo furoshiki and smashed them with two sharp slams of the hammer. She shook the pieces out of the furoshiki into the box and wrapped the box in the indigo cloth. “Please pour,” she said to her sister.

Two days later Akiko was due at her volunteer job at the tourist information office’s kiosk. She left very early, carrying the indigo furoshiki, and got off the bus at the Castle, several stops before the train station. The cherry petals had just fallen from the trees. She walked through the pink carpet on the path from the Castle keep to the garden, enjoying the tattered scraps that were all that remained of the beauty of the blossoms. She regretted not seeing them the week before in full flower, but knew that she wouldn’t have been able to bear the noisy, drunken crowds. She went slowly from the garden out to the street and decided to walk down Otemae-dori to the station, even though she knew it would take her twice as long as it should. She had lunch at a coffee shop a block from the station, grateful to sit and rest her tired feet and aching knees. She arrived at the kiosk by one.

Ichikawa-san was struggling with a tall blond couple who had come from the Castle and wanted to know how to get to Kyoto and climb Mt. Hiei by the end of the day. When Ichikawa-san saw Akiko, she stammered, “Ah, here is Mrs. Imagawa. She lived in America. She can help you.”

The young Germans began telling her what they wanted in their almost perfect but heavily accented English. Akiko smiled and reached for a train schedule as she walked into the kiosk, where she slipped the furoshiki under the counter, out of sight. After she finished explaining the schedules, she and Ichikawa-san stood and waved goodbye. “I’m surprised they didn’t want to see Kyoto and climb Mt. Fuji by the end of the day,” said Akiko, with her public smile still in place.

Ichikawa-san was still giggling when a group of businessmen entered the station. They were coming from the White Heron Grand, Himeji’s best hotel, across the street. The three Japanese hosts had a tall, beleaguered-looking American with them. Akiko guessed that he had been treated to a fancy lunch of unfamiliar foods and forced to drink more than he was used to in the middle of the day. Her guesses were confirmed when one of the group urged the others towards the information counter saying, “Come on, we can’t let Samueruson-san leave Himeji without seeing the most beautiful castle in Japan,” repeating this in broken English.

Samuelson, thinking no one heard him, muttered, “But I already saw it—from the train.”

“Do you have anything in English?” the youngest of the Japanese demanded.

Akiko told him she did but made sure she handed the English language pamphlet directly to the American, telling him, “It’s called the White Heron Castle, and it really is considered the most beautiful castle in Japan. We Japanese like to make lists and rankings of things. This one won the most beautiful castle category. Everybody agrees.”

“Oh, thank you. This day has been a bit much. We were on our way to Osaka, but my hosts decided we had to get off the train here for lunch.”

“Where are you coming from?”

“We were visiting a fish farm site on the other side of the Inland Sea. Outside Matsu—Oh, I forget.”

“Well, it was probably either Takamatsu or Matsuyama.”

“The first.”

“Good luck getting to Osaka.”

“Thanks. I think I’ll be okay if I don’t have to drink any more.”

“You’ll be fine, and the Castle really is lovely. I bet they pile you in a taxi and give you the grand tour before you catch the train again.”

“Thanks. Did you live in the States?”

“Yes, Columbus and San Francisco.”

“I’m Pete Samuelson. I’m from Cleveland.”

“Say hello to Ohio for me. My sister loves the Good Morning Ohio joke that I’m sure you’ve heard from this group.”

Samuelson laughed, “Oh, yes! I’m so glad we met you.”

Impatient with all the English, the oldest of the three Japanese businessmen asked Akiko if they had time to see the Castle and still make the three-o’clock Shinkansen bullet train to Osaka. When she answered affirmatively, they hauled Samuelson out into the taxi line and folded him into the front seat of a cab, the three of them climbing int

o the back.

When they were gone, Ichikawa-san said, “It was exhausting just watching them and trying to answer their questions. I hope that gaijin is okay.”

Akiko laughed, “He’ll have great stories to tell when he gets home.”

On her way home Akiko got off the bus at the Castle, entered the garden, and went straight to the far corner, where a bamboo screen hid equipment. She found the gardener there, as she thought she would.

“Imagawa-san, can I help you?” he asked. “Did one of your foreign tourists lose something?”

“No, Higuchi-san, I have a favor to ask.” Akiko nodded in the direction of the branches and twigs stacked against the back wall of his work area. “Now that the cherry blossoms are gone, and we have fewer visitors, I know you’ll be burning everything from your spring pruning. Would you please add this to the fire?”

“Of course, Imagawa-san. Is there anything else I can do?” he said, accepting the furoshiki with both hands.

“No, but thank you. I truly appreciate it.” Akiko smiled with gratitude and turned to leave. As she walked away, she made herself think only about Higuchi-san, and how hard he worked to keep the cherry trees healthy and blossoming spectacularly far into advanced old age. She retraced her steps through the beautiful complex passages that were the result of his meticulous work, left the Castle grounds, and headed for the bus stop.

2. GENTARO

Berkeley, 1999

The second day she brought the photograph and they sat together at lunch looking at it. The day before all he could do was look at her scars—one cut across the bottom of her chin like an upside-down scimitar and the other slashed from the forehead across her right eyebrow and past her eye to her cheekbone. It had taken him a while to hear what she was saying. Finally, he realized that she was laying claim to him, reminding him of the Peters School in Pacific Heights.

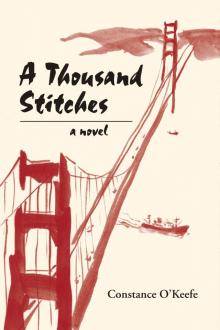

A Thousand Stitches

A Thousand Stitches